Two Mississippi Museums Making A Difference

Black History Month kicks off with the Mid South Foundation and Two Mississippi Museums free admissions day, honoring its role as a place of truth and reconciliation

Few Mississippians believed that two new museums would paint an honest picture of the state’s history.

“There was a lot of skepticism, especially in the black community about whether or not an accurate civil rights museum could be created,” said director Michael Morris who was a Jackson State University (JSU) student at the time. “People were very outspoken about making sure that museum was a truthful reflection of the past.”

Morris caught wind of the project from civil rights historian and JSU professor Dr. Robby Luckket, who also leads JSU’s Margaret Walker Center, an archive and museum dedicated to African American history and culture.

“People came to those meetings armed with their stories and information about what they know to have taken place. And ready to challenge the powers that be at that time to tell the stories with all of their complexity…. telling the unvarnished truth,” said Morris.

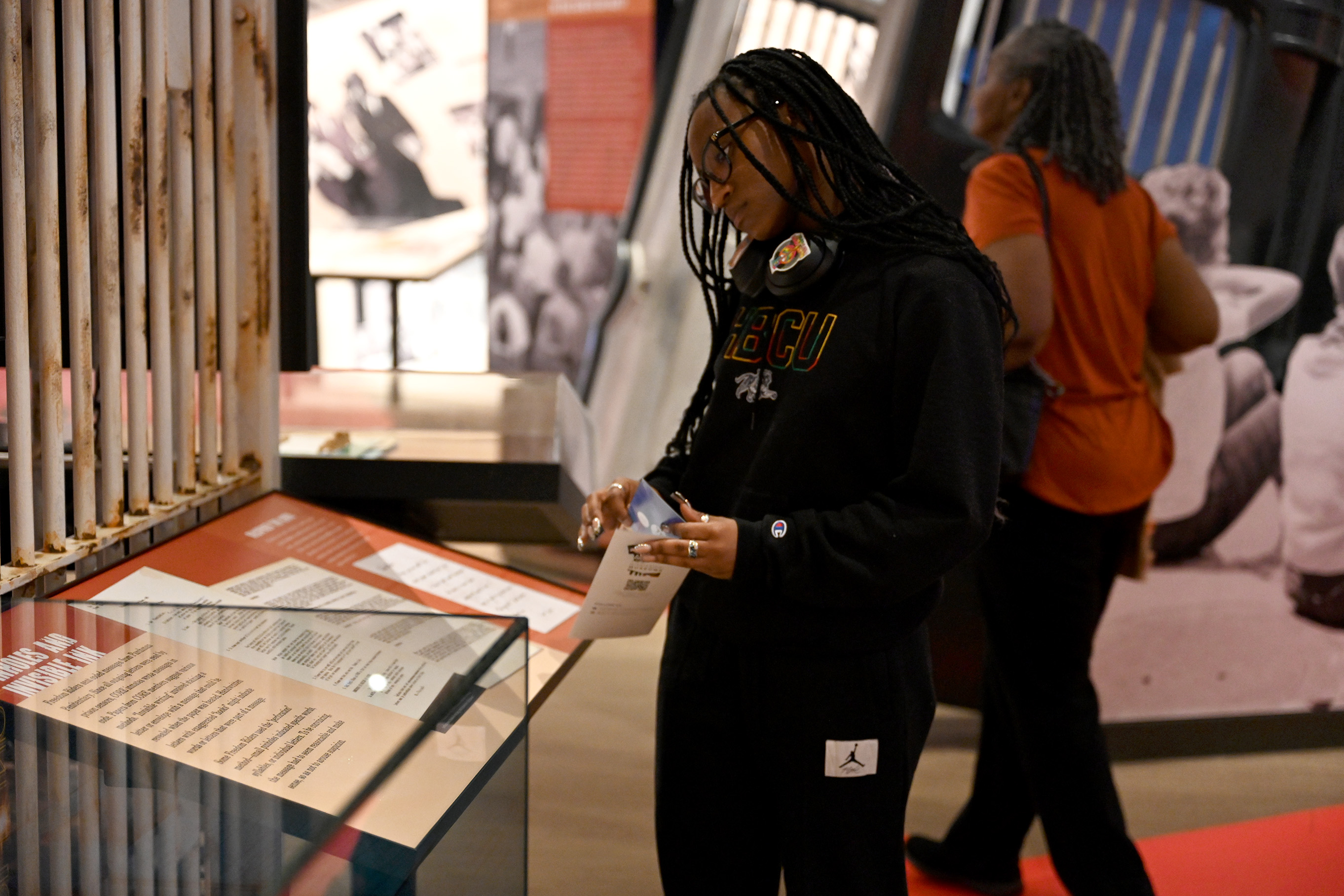

Today the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and the Museum of Mississippi History are significant cultural landmarks and sources of state pride. Since opening, more than 600,000 visitors have walked the museum halls.

The museums’ creation was not a smooth path. It faced numerous challenges, including funding issues, site selection controversies, and political debates. A diverse cohort of Mississippians bridge countless differences to erect an unflinching dive into Mississippi’s storied civil rights legacy and native American eviction.

The official ribbon-cutting ceremony in 2017 was graced by prominent figures, including Myrlie Evers, the wife of Medgar Evers—a civil rights activist assassinated in 1963. In her speech, she called the two museums “separate but equal” and that “one is not complete without the other.”

Can Museums Make A Difference?

More than bridging racial divides, museums can connect people from different cultures, ideologies, and creeds by offering a glimpse into the lives of people.

In Mississippi, the museums have proven to be more than mere repositories of historical artifacts. They are places that foster civic discussion, learning, and inspiration. They celebrate the diversity of Mississippi’s history and inspire individuals to work towards a common dream.

As a result, the Foundation for the Mid South supports the Two Mississippi Museums as an ally of the Mississippi Truth and Racial Healing Transformation (TRHT) initiative working to unite communities through dialogue and trust-building.

Through the initiative, Greek letter organizations, churches, and nonprofits engage in racial healing, centering practices, tools, and collaborations for dismantling persistent poverty, deeply rooted inequities, and racism.

Museums are natural partners to racial healing and central to W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s pioneering model convening communities across America for healing, trust, and relationship building.

Amid growing political and cultural conflicts, museums have a responsibility to welcome an accurate representation of communities. According to Alpha Oumar, a museum scholar, deep problems can be solved by collaborating with the leaders and cultural traditions. A crucial benefit is the creation of awareness. By involving the community, diverse cultures are appreciated for their contributions.

Every week the Two Mississippi Museums host a lecture series uniting people throughout the state. According to Morris, “Most Wednesdays I see one of the most diverse audiences in the state. People from all backgrounds coming together to listen to somebody tell a story, which is so Mississippi.”

Mississippi A Civil Rights Pioneer

Mississippi played a pioneering role in the national movement for civil rights. Known for its particularly brutal oppression, infamous violence during Mississippi’s civil rights era opened the eyes of the nation. Civil Rights leaders set up camp in Mississippi for that precise reason.

Most histories recall the lynching of 14-year-old Emmet Till in 1955, and his mother’s decision to share with the world his battered body. That same year, three black leaders were also murdered in Mississippi: Rev. George Lee, Gus Courts, and Lamar Smith.

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum underscores what civil rights leaders understood at the time –that civil rights breakthroughs in Mississippi have the best chance to lead to more freedoms for everyone else.

The idea for the Civil Rights Museum was birthed on the campus of Tougaloo College with Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and young activists like the late Hollis Watikns, one of the first young full-time workers with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

“These veterans of a movement had been collecting their papers. They understood at that moment when the movement was happening, the importance of what they were doing. And so they decided to collect various papers and documentation that demonstrated what they had gone through, this included artifacts as well.”

Reuben V. Anderson, Mississippi’s first African American Supreme Court Justice, and former Mississippi Governor William Winter led the charge. The two approached Governor Haley Barbour and pitched the idea of building the two museums side by side in downtown Jackson.

Former Governor Haley Barbour ran with the idea. According to the Clarion Ledger, the Republican convinced the legislature to approve $38 million in funding for “two entities under a single roof.”

In its making, the Two Mississippi Museums offer a glimpse into the power of grassroots community building, reconciliation, and truth-telling to solve problems when tensions rule, competing priorities clash and common ground is hard to find.

“It’s a reflection of the entire state. You’re going to see something about the Greenwood movement, the Macomb movement, and what took place here in Jackson, “ said Morris. “We were able to give you an overview of the complex nature of the civil rights movement in this state between the years 1945 and 1975.”